"These are the oldest solid materials ever found, and

they tell us about how stars formed in our galaxy. They're solid samples

of stars."

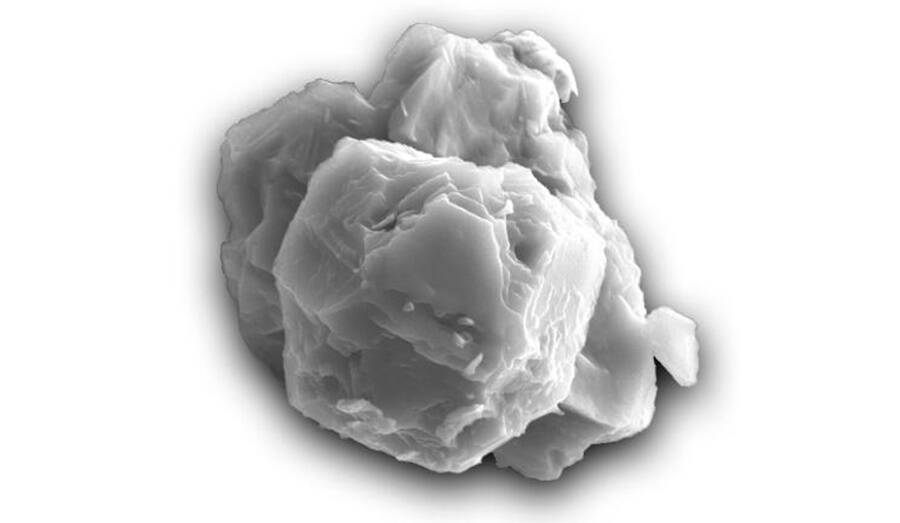

Janaina N. AvilaResearchers discovered 7 billion-year-old stardust from a meteorite that landed on Earth 50 years ago.

On Sept. 28, 1969, a meteorite hurling toward Earth landed near Murchison, Victoria, in Australia. Though the 220-pound meteorite’s crash-landing on our planet isn’t itself news, the interstellar material it accidentally brought along with it certainly is.

As reported by CNN, a new study examining the meteorite revealed it had carried stardust from outer space that formed between 5 and 7 billion years ago, making both the meteorite and its stardust the oldest solid material ever found on Earth. “This is one of the most exciting studies I’ve worked on,” said Philipp Heck, the study’s lead author and a curator at the Field Museum in Chicago. “These are the oldest solid materials ever found, and they tell us about how stars formed in our galaxy. They’re solid samples of stars.”

Space is filled with stardust, but ancient presolar grains — aka dust grains that predate our sun — have never been found in Earth’s rocks, so the discovery of its existence is incredibly significant.

By analyzing stardust, researchers can take a closer look at the

history of our galaxy. They may also be able to learn the origin of our

bodies’ carbon and the oxygen that we breathe in.

Wikimedia CommonsA fragment from the Murchison meteorite.

Researchers working on the study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzed isolated samples of presolar grains taken from the Murchison meteorite.

Most presolar grains measure less than a micron in length but the presolar grains derived from the Murchison meteorite were much bigger, measuring two to 30 microns and visible under an optical microscope lens. These larger grains are called “boulders.” However, the process of isolating the rock’s fragments into presolar grains took some extra effort from researchers.

“It starts with crushing fragments of the meteorite down into a powder,” explained co-author Jennika Greer, who is a graduate student at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago. “Once all the pieces are segregated, it’s a kind of paste, and it has a pungent characteristic. It smells like rotten peanut butter.”

After the paste is dissolved in acid, the presolar grains are revealed. Isolating these grains allowed researchers to determine how old the stardust was and the type of star it came from.“I compare this with putting out a bucket in a rainstorm,” Heck said. “Assuming the rainfall is constant, the amount of water that accumulates in the bucket tells you how long it was exposed.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Murchison meteorite weighs 220 pounds and was recovered in Australia.

The results of the analysis were stunning. Many of the grains were estimated to be between 4.6 and 4.9 billion years old, while some others were concluded to be much older, likely more than 5.5 billion years old.“There was a time before the start of the solar system when more stars formed than normal,” Heck said.

The finding is a key component in the understanding of star formation among space scientists.

“Some people think that the star formation rate of the galaxy is constant,” Heck said. “But thanks to these grains, we now have direct evidence for a period of enhanced star formation in our galaxy seven billion years ago with samples from meteorites. This is one of the key findings of our study.”Soon, we’ll figure out more ways to unlock the world’s mysteries with help from the stars.

No comments:

Post a Comment