The risk of death from an encounter with a shark may be grossly exaggerated in popular culture, but that's likely small consolation to a man who lived and died 3,000 years ago. His remains now represent the oldest known shark victim ever found.

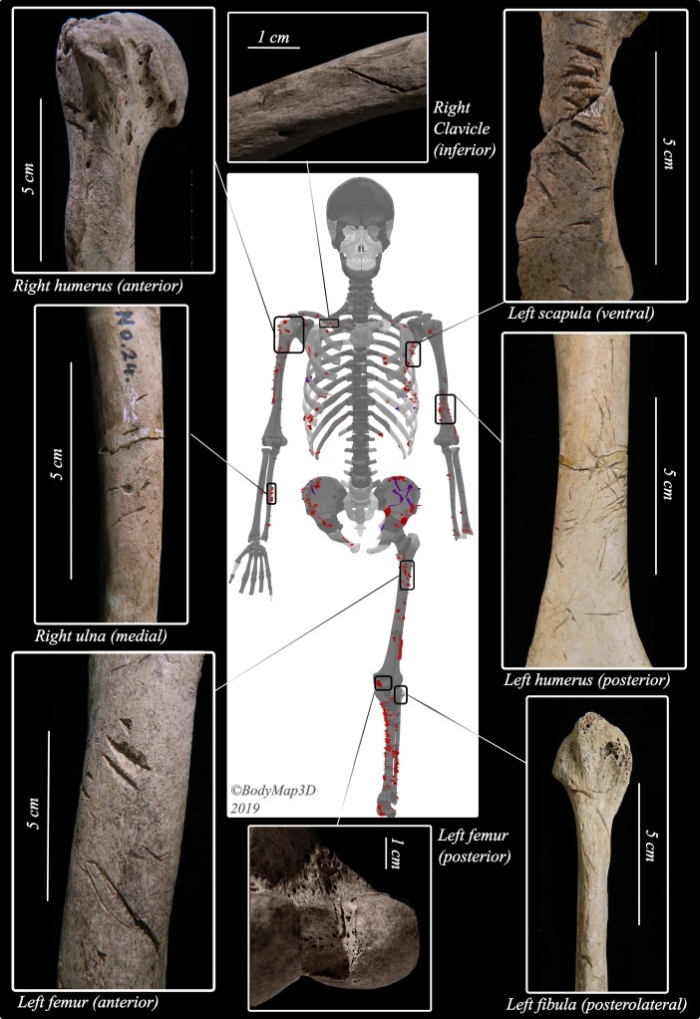

According to an analysis of his bones, the man had a particularly nasty meeting with one of the marine predators, in the Seto Inland Sea of the Japanese archipelago. Nearly 800 wounds scored his skeleton, none of which showed any signs of healing - suggesting, strongly, that the encounter was a fatal one.

The bones, recovered from the Tsukumo Shell-mound archaeological site near the Seto Inland Sea, were first excavated early in the 20th century CE, but an explanation for the man's injuries remained elusive.

Then, the bones were rediscovered by archaeologists J. Alyssa White and Rick Schulting of the University of Oxford in the UK, who were investigating violence in prehistoric Japan.

"We were initially flummoxed by what could have caused at least 790 deep, serrated injuries to this man. There were so many injuries and yet he was buried in the community burial ground, the Tsukumo Shell-mound cemetery site," they said.

"The injuries were mainly confined to the arms, legs, and front of the chest and abdomen. Through a process of elimination, we ruled out human conflict and more commonly-reported animal predators or scavengers."

The lesions on the bones of the man, known only as Tsukumo No. 24, were certainly curious. They were sharp-edged, and curved, which the researchers found inconsistent with the stone tools in use at the time.

In addition, his left hand and right leg were missing, and his left leg had been placed on top of his body in an inverted position for burial.

Shark encounters are rarely seen on the archaeological record, but the wounds didn't seem to match any other kind of animal encounter either. The archaeologists turned to marine biologist George Burgess of the Florida Museum of Natural History's Florida Program for Shark Research, as well as records of shark encounters, to see if No. 24's wounds matched up there.

"Given the injuries, he was clearly the victim of a shark attack," White and Schulting said.

"The man may well have been fishing with companions at the time, since he was recovered quickly. And, based on the character and distribution of the tooth marks, the most likely species responsible was either a tiger (Galeocerdo cuvier) or white shark (Carcharodon carcharias)."

It was impossible to narrow the species down further, since the bite marks are so numerous and overlapping that a diagnostic jaw shape cannot be inferred.

The team also performed bioarchaeological evaluations of the bones, to determine when No. 24 had lived, confirm his sex, and work out how old he was at time of death.

According to the researchers' analysis, the man was young to middle-aged at time of death, and he lived around 1370 to 1010 BCE. His remains had been recovered shortly after the shark encounter, and interred in the cemetery of his people.

Although the encounter seems violent, the researchers believe that the man would have died quite quickly. Given the number of bites that reached the man's bones, his femoral arteries would have been severed early, resulting in rapid death from hypovolemic shock, which happens when the body quickly loses at least one fifth of its blood.

The research offers a rare insight into the risks of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

"The attack on Tsukumo No. 24 highlights the risks of marine fishing and shellfish diving or, perhaps, the risks of opportunistic hunting of sharks drawn to blood while fishing," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"Humans have a long, shared history with sharks, and this is one of the relatively rare instances when humans were on their menu and not the reverse."

The research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

No comments:

Post a Comment