Like Milky Way, the Andromeda galaxy is a spiral galaxy. But the area rich in stars near that galaxy’s center doesn’t look like it should. The orbits of these stars take on an odd, ovalish shape like someone stretched out a wad of Silly Putty.

A new study led by CU Boulder has solved a decades-old mystery surrounding a strangely-shaped cluster of stars at the heart of the Andromeda Galaxy. It suggests that supermassive black holes at their cores release a strong gravitational kick during galaxy collision, powerful enough to knock millions of stars into wonky orbits.

The first view of the Andromeda galaxy was expected to show a supermassive black hole surrounded by a relatively symmetric cluster of stars. But, they found a huge, elongated mass.

What is the reason behind this?

Scientists may have found the answer.

Using computer simulations, scientists tracked what happens when two supermassive black holes go crashing together. Their calculations suggest that the force generated by such a merger could bend and pull the orbits of stars near a galactic center, creating that telltale elongated pattern.

Tatsuya Akiba, a lead author of the study and a graduate student in astrophysics, said, “When galaxies merge, their supermassive black holes are going to come together and eventually become a single black hole. We wanted to know: What are the consequences of that?”

“The findings help to reveal some of the forces that may be driving the diversity of the estimated two trillion galaxies in the universe today––some of which look a lot like the spiral-shaped Milky Way, while others look more like footballs or irregular blobs.”

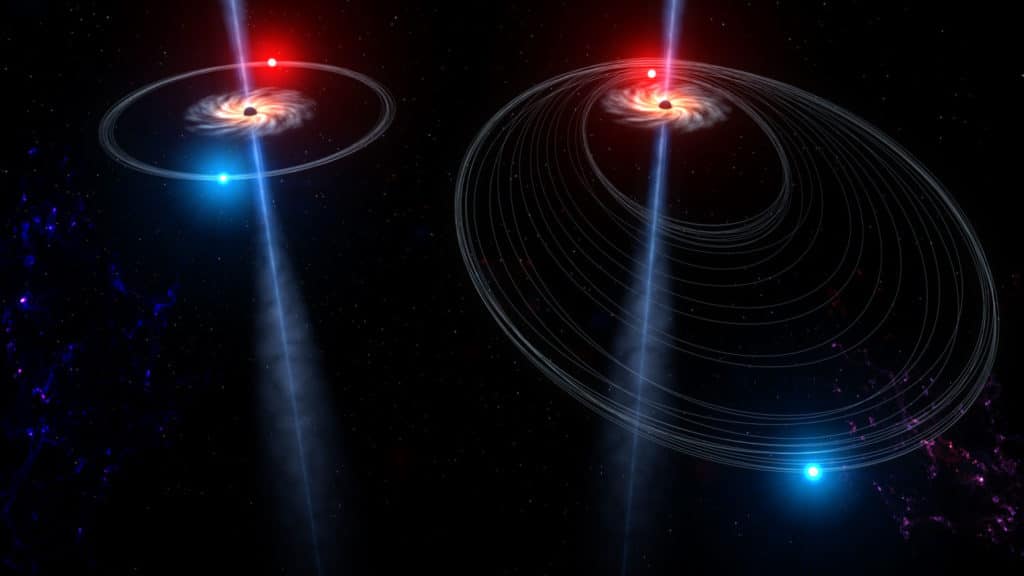

“Mergers may play an important role in shaping these masses of stars: When galaxies collide, the black holes at the centers may begin to spin around each other, moving faster and faster until they eventually slam together. In the process, they release huge pulses of gravitational waves or literal ripples in the fabric of space and time.”

“Those gravitational waves will carry momentum away from the remaining black hole, and you get a recoil, like the recoil of a gun.”

Scientists wanted to determine what such recoil could do to stars within 1 parsec. Andromeda galaxy stretches tens of thousands of parsecs from end to end.

Using computer models, scientists built models of fake galactic centers containing hundreds of stars. They then kicked the central black hole to simulate the recoil from gravitational waves.

Ann-Marie Madigan, a fellow of JILA, a joint research institute between CU Boulder, said, “the gravitational waves produced by this kind of disastrous collision won’t affect the stars in a galaxy directly. But the recoil will throw the remaining supermassive black hole back through space––at speeds that can reach millions of miles per hour, not bad for a body with mass millions or billions of times greater than that of Earth’s sun.”

“If you’re a supermassive black hole, and you start moving at thousands of kilometers per second, you can escape the galaxy you’re living in.”

When black holes don’t escape, however, the team discovered they might pull on the orbits of the stars right around them, causing those orbits to stretch out. The result winds up looking a lot like the shape scientists see at the center of Andromeda.

Scientists noted, “We want to grow the simulations so we can directly compare their computer results to that real-life galaxy core––which contains many times more stars. The findings might also help scientists to understand the unusual happenings around other objects in the universe, such as planets orbiting mysterious bodies called neutron stars.”

Madigan said, “This idea––if you’re in orbit around a central object and that object suddenly flies off––can be scaled down to examine lots of different systems.”

1 comment:

It would be interesting to find a pattern between the total fusion energy of black holes and the relationship between the number of increases in the energy of cosmic bodies orbiting them.

Post a Comment